This is a revolution in the old sense, a coming back around again, but also a new turn.

Many think of the melting clocks and giraffed elephants of Dalí when surrealism is mentioned. And though it may be a newish term denoting this style, it is rooted in an old tradition. Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud brought to our attention the fact that myth and its subsequent medium, literature, were human endeavors grown out of dreamland. When we dream, our minds naturally muddle reality and place strange things in strange places. And so it is natural to have stories and images depicting such things as a dominating force in all human endeavors. It is a recycling of the images we see in our mind that are a patchwork of those we overload our sight and thoughts with on a daily basis. At its essence, it is a way to get to know ourselves.

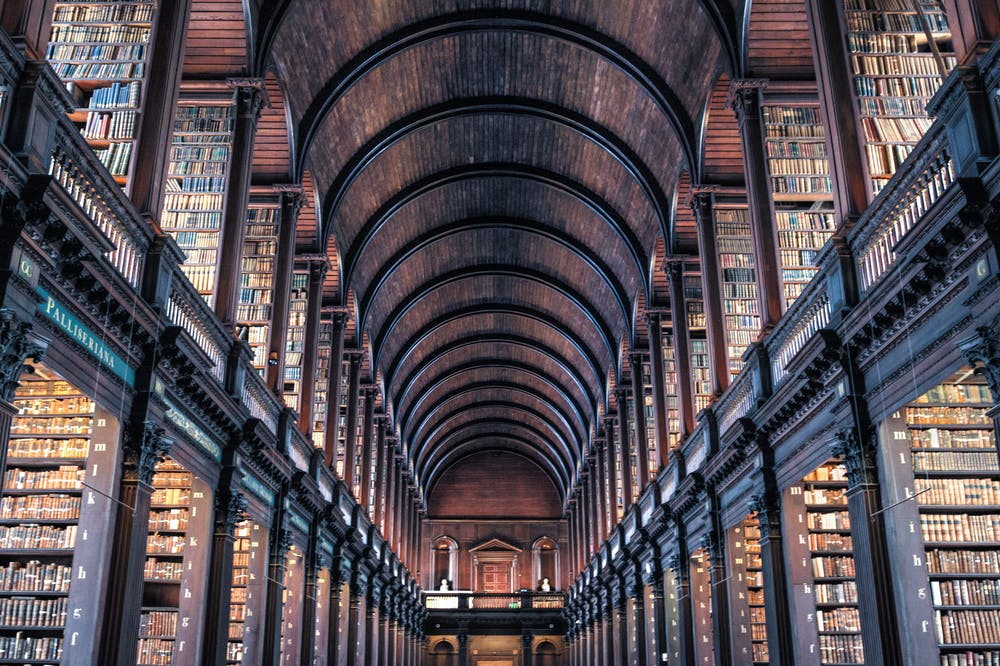

Through the ages most of our major, lasting works have been surreal in some sense or another. Think most religions — the battling gods of the Vedas, the animorphic deities of the Egyptians, the grail cycle in Arthurian legend, and even Scientology today. They nearly all go past the reality we know and delve into strange worlds. The weird fiction of century’s past, horror, and the present Fantasy and SciFi (to an extent) genres are ones born of this tradition as well.

Of course realism has too been a factor throughout. The sculptures of Greece and Rome, Renaissance paintings, sagas and histories, much Victorian literature, the American giants such as Hemingway and Steinbeck, and so on. This seems to dominate our culture today. We have crime dramas, mockumentaries, sitcoms, and reality TV aplenty. Nonetheless, as I’ve said, the surrealist tradition is coming around again. Recent mainstream shows, most notably Lost, but also those like Dr. Who, have brought it back into the public eye. No more is fantasy the realm solely of the fanboy still living in his parent’s basement.

And in art we have the escapists such as Josephine Wall, the studies in subconscious by Alex Grey and his peers, and many hopeful (or not) futurists that explore the strange worlds that science might unveil. Not to mention the rise in 3D design.

The most prominent front however is in cinema. And here the line between reality and surreality is beginning to blur more than ever. Our fears are no longer primitive as a race, our concerns for more than familial or communal comfort. Think of stories such as Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly, in which a perfectly plausible synthetic drug opens up dreamlike worlds to the conscious observer. Or Richard Linklater’s Waking Life, an examination of death, dreams, and conscious life, and their relationship, often an undistinguishable one, with one another. Ingmar Bergman also steps into this realm often. And then there are the giants like Tim Burton or the novelist Neil Gaiman. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey howeveriscertainly the grandfather of the direction in which the genre is headed.

Explorations of consciousness and existence, small instances of Man in the context of the whole universe and within the vast realm of his own brain (two planes which seem to become more and more interconnected or symbolic of each other with every new leap in science and technology), are to be dominant. Rather than the past/present focused myths of the world’s former primitive/civilized humans, the new human is more innovative than ever and so he observes beyond his heritage and himself, extending his vision deep into the future.

Within the past five or six years, a few fairly successful movies in particular have fit this mold. Darren Aronofsky’s The Fountain, for example, encompasses all spectrums of time and reality, but focuses primarily on one man’s journey caring for his cancer-ridden wife. Danny Boyle’s Sunshine (2007), also, is a movie in which the Sun is dying and so a few brave men must drive a cube-shaped bomb into its heart in order to fire it up again and save humanity. But not before they meet a man, more a creature now, that has seen the light (literally) and tries to prevent their progress. Then there’s Terrence Malick’s deeply existential Tree of Life (2011), a study of creation and destruction on both micro and macro levels. Most recently is Melancholia (2011) by Lars von Trier, which focuses on a woman’s wedding, who suffers from depression, and the excitement surrounding a planet passing through the Earth’s orbit. Many of these situations are plausible to an extent by science’s standards, but the way they are dealt with is entirely otherworldly.

Surrealism, myth, fantasy, whatever you might call it, has always dealt with the fear of darkness and the unknown that man must face on a daily basis. Now that this world has been conquered all that’s left is the vastness of the universe itself, and the complexity of the mind. Here we are left, to ponder, to worry, and to hope. And yet we deal with the stress all the same — through the imagination. And so the patchwork tapestry will never be finished until the whole of the universe is conquered, or as many of our contempory surrealists consider, our race extinct. Until then, the wheel continues to turn.

P.S. It doesn't have to end like this

Between Pages is a newsletter for readers like you. Every month I'll send you some notes just like these from my latest read.